In 2007, Walk Score appeared out of nowhere and built a way of looking at the world that was so useful and intuitive as to become, at once, completely manifest and familiar. By pulling the shapeless abstraction of “walkability” out of the sky and giving it a life through numbers, a life that could now be communicated and compared and concretely aspired to, Walk Score democratized the esoteric field of urban planning and built a tool everyone could use.

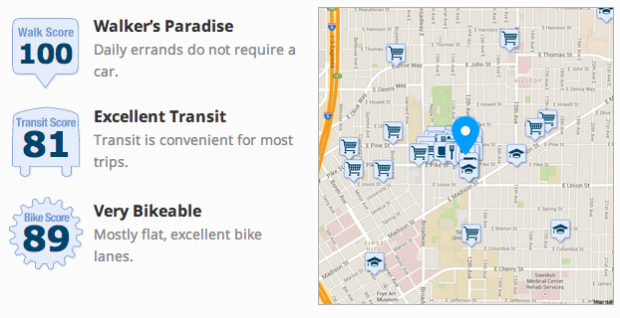

Next came Transit Score and Bike Score, which expanded Walk Score’s reach by incorporating a new perspective on a location’s bikeability and transit-friendliness. And now Walk Score is changing how people search for apartments and rentals, using its products to move beyond the symbolic and into the experiential.

In this sense, Walk Score becomes a portrait of liveability, an identification and promotion of the services and surfaces around which people weave meaning and identity. It becomes a platform for presenting collective knowledge, where cities have firmer, clearer shapes, where people can think, reflect, create, explore, argue, and love.

This is no accident: it’s mission-driven. Matt Lerner, Co-Founder and CTO of Walk Score, said:

“We always say what’s unique about Walk Score is the combination of innovative software with our mission. For me, personally, as someone who loves software, what I love about Walk Score is finding something I can apply software to that is making a difference in the world that I am passionate about. For me, it was about finding a combination of what I love and what I’m good at, which is software, and a problem in the world that I really care about, which is urban planning.”

“We always say what’s unique about Walk Score is the combination of innovative software with our mission. For me, personally, as someone who loves software, what I love about Walk Score is finding something I can apply software to that is making a difference in the world that I am passionate about. For me, it was about finding a combination of what I love and what I’m good at, which is software, and a problem in the world that I really care about, which is urban planning.”

We spoke with Matt about the world of Walk Score.

Why was Walk Score built?

When I left Microsoft, I got together with Mike Mathieu, who has been one of my main career mentors, and we both had a bunch of different ideas for software that we thought would make some kind of positive difference in the world. And so for about a year, we tried to do a couple different projects per month and one of the projects that grew out of that was Walk Score. We built the first prototype of Walk Score in a couple of months and I emailed it to 15 people for feedback and the next day we had 150,000 unique visitors on the site.

So what we learned from that is that you can’t predict the hits. It was a really pleasant surprise to do this thing that was a kind of urban planning-related site and find out that people actually cared about it.

When you were building out these ideas, were you working off of a plan or was it ad hoc?

It was basically personal passion. I’m really passionate about neighborhoods and how you measure the quality of neighborhoods and whether things are getting better or worse and what things drive quality of life in neighborhoods. So we were doing everything fromwhat would a social network for neighborhoods look like, which is what Next Door has ended up being, but we sorta hit upon Walk Score because there’s the saying “what you measure matters” and there was kind of no measurement for this big urban planning trend that I was personally really passionate about because I grew up in Topeka, Kansas, and didn’t even know urban planning existed. So here I am growing up in Topeka and watching a mall get put on the fringe of the town — and we didn’t just have a Wal-Mart, we had a Hypermart come into the fringe of town, we had a big highway going right through our downtown — and I just thought that cities were either cool or not and you didn’t have much control over it. And then I got older and realized that there’s this whole discipline called urban planning and there’s this thing that urban planners have been talking about for decades called walkability and it’s a really broad thing. It means what do you live near, what’s your commute like, how can you can access your city on public transit and bicycling, are you near the people and places you love. But there was no way to measure that and we wanted to make walkability part of how people decided where to live, so we decided to put a number on it.

And there’s a really interesting thing. So Alan Durning, who was one of the inspirations for Walk Score…I am really big into mentorship. Mike Mathieu, who I started this with was a big mentor of mine and Alan Durning, who started the Sightline Institute was a big mentor of mine, and Alan inspired Walk Score. He has a saying that the changes that matter most are very slow changes. So life expectancy, energy use, climate change, these are all very slow changes. We’re all tuned in to pay attention to fast changes, and so one of the things we did with Walk Score was to take this really slow change, which is this mega-trend toward walkability, but we made it really personal by putting a number on it for your house, and that’s how we got so many people interested in it.

Do you feel like Walk Score is having an effect on urban planning or development today?

Do you feel like Walk Score is having an effect on urban planning or development today?

Yes, because once you put a number on something, it unlocks a whole bunch of different things. One is that we just announced today that we show more than 20,000,000 scores per day, so that’s 14,000 scores per second.

That’s amazing.

So it’s really become part of…you know, it’s on Zillow, it’s on Trulia, and those are the two biggest real estate sites. We’re on over 30,000 real estate sites and I reason I like it is because of two reasons: I grew up in Kansas and now people in Topeka and Omaha are starting to see this thing and ask “what is it?” and “does it matter?” and, separately, we’ve had all of these academics whose research was unlocked by our data because once you put a number on something, people can do research with it.

An economist in Portland, this really cool guy named Joe Cortright, did a study that showed one point of Walk Score is worth about $3,000 of home value. So as soon as the financial data is out there, it’s easier for people to say “well, I might not care about the environment, but I want to make a good investment in my home and these walkable places seem like a better investment.” So our whole theory of change is to increase the demand for walkable neighborhoods, increase the development of walkable neighborhoods, and increase America’s Walk Score.

Are you surprised so far by its success?

Good question. Initially, I was surprised because we felt early. We started it in 2007 and it’s amazing, seven years later, if you just look at what’s happened in Seattle, what’s happened in Portland, and you look at the home prices in walkable neighborhoods, what’s interesting now is consumer demand, especially if you look at Millennials. The Rockefeller Foundation just did a study that found that 4/5 of Millennials want to live close to amenities and in places with transportation options. So basically 4/5 of Millennials want walkable neighborhoods, so now that consumer demand is really there. Personally, when I go out and talk about Walk Score, I’m getting a lot of questions now about affordability because the demand for walkable neighborhoods has gotten so high and the supply of walkable housing is still so low that the prices are really high.

Is your metric pricing people out of walkable neighborhoods?

Architects do these visual preference surveys where they show people two pictures and if you show Americans a suburban McMansion and a walkable condo, and about half pick the McMansion and half pick the walkable condo. It’s sort of like our politics, kind of evenly split. But the problem is that only about 20% of our housing stock is walkable, and that’s why walkable neighborhoods are so expensive. Really, we have to create more walkable housing and part of the way we create more walkable housing is to have more diverse walkable housing so you have things like backyard cottages, micro-housing, all of the urban infill. These are all ways to basically create more walkable housing and that’s the only way to bring the prices down.

You have a robust community around Walk Score. Have your users used Walk Score in unexpected ways?

Yes. Some of the governmental uses have been really interesting. Michigan is using Walk Score to allocate low income housing tax credits. Cars are the second largest household expense after housing, and part of what happened in the 2008 housing bust was that when gas prices went up, people suddenly couldn’t afford their mortgages anymore. So Michigan wants to create walkable housing in low income neighborhoods so people can spend less on transportation. They are actually using our data to award tax credits for low income housing. Some of the things like that are special to me personally because they are using Walk Score to solve this affordability problem.

When you founded Walk Score, was that the kind of effect you were hoping for at some point?

No. The thing that we wanted to do…the things we want to do is express what walkability is in terms of our product features.

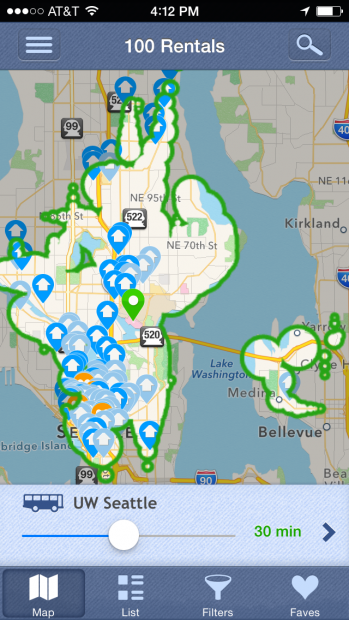

So let’s say I’m looking for an apartment in Seattle…our whole goal is to let people find a place to live near the people they love with a short commute, near public transit, where th

ey can explore the city on bicycle. So I could say that I work on the University of Washington in Seattle and I want to take transit in 30 minutes: where can I live? And so this is a visualization of all the places I can live and still get to the University of Washington in 30 minutes on transit.

And maybe I have a roommate who works in downtown Seattle and bike there in half an hour. I can add that and see apartments where we can both live and have a short commute. Or I can say things like “I want to have a coffee shop within ten minutes” and “I want a Zip Car within ten minutes” and “I want a grocery store within ten minutes” and now here are all of the apartments that have coffee shops and Zip Cars and grocery stores within ten minutes. And then if I zoom in and pick a listing, what we have are scores, the Walk Score that measures how walkable your house is, a Transit Score that measures how well your house is served by public transit, a Bike Score that measures how bikeable your house is, and these maps that show you what parts of the city you can explore, we show you nearby transit routes, we show you nearby car shares, and you can do some pretty cool stuff.

If I’m moving to Washington, D.C., a place that, unlike Seattle, has a good public transit network, I can just say “Find me all of the apartments that are within a ten minute walk of the subway” and this is a map of all of the subway stations in DC that I can get to in ten minutes. So you can see how our goal is to express what urban planners mean by walkability in terms of the features of a product.

How do these features get built?

What’s exciting to me about what we’re doing is that we’re all software professionals who have found this place where we can make a difference. Everyone rides their bike to work here. Everyone is really passionate about our mission and what makes us different as a start-up is…here’s a good example. When we launched our Bike Score, I was on NPR with Melissa Block as a spokesman for biking in this country!

And what’s nice about that is that our engineer who built Bike Score, who rides his Surly fixie to work everyday, he just built the new metric for measuring bikeability and the reason that is so important to us is that anyone in business, if you have a goal you want to achieve, you have to be measuring it. And that’s why we have our scores.

If someone wanted to work at Walk Score, what kind of skills should they develop?

Well, maybe there are two answers. One is that everyone knows it’s hard to hire software engineers right now. But the other thing is that I am interested in the people who will start the next Walk Score and what skills do you need to start something. What’s funny about my own experience — this is my second startup, I also started a voter registration group in 2004 that got kind of big — and every single one of those has happened totally organically, aka randomly, just based on something that I cared about. Like Walk Score starting with this passion around walkable neighborhoods and meeting other people who were passionate about it, and then getting some early feedback that people actually care about it this stuff, and then deciding to really go for it. And it’s interesting now too. Look at younger people starting companies. Almost all of the companies now that are starting are described as mission-driven companies. You hear young entrepreneurs in San Francisco talk about not making a lot of money but doing something that makes a difference. A lot of people criticize that as business as usual with a different veneer, but you know, people I think are the most happy, most interesting, and most productive are the people who have found something that they really care about and they figured out how to apply whatever their unique skill in life is to those problems.

So there is some hope for the future?

I’m hopeful!

CreativeLive is quite proud of its San Francisco Walk Score and its Seattle Walk Score.